- Blog

- Captions: A Window to the World

Aug 30, 2023 | Read time 7 min

Captions: A Window to the World

Captions offer many benefits, from inclusivity to accessibility. Let's delve into the evolution of captions, their advantages, and the power of ASR’s role in enhancing accessibility.

Craving More on Captions 👇

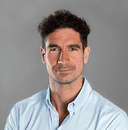

Captions are familiar to almost all of us. Without them, (if you were unable to hear the sound) you would not know that Ron Swanson is, in fact, despite appearances, laughing in the below image. Laughing deep deep down inside.

There are actually some related terms here that are sometimes used interchangeably:

Subtitles – display a transcript of the dialogue spoken, and can be either in the original language or translated into others.

Captions – captions not only show dialogue, but also key audio events happening on screen. This might include descriptions of changes in music, or noises not seen within the frame (as with the example above). They provide an accessible way to follow along with media without the need for sound. There are two types of captioning (explained in more detail on this blog):

Open Captions – these captions exist on the same ‘track’ as the media itself. They are effectively hardcoded into the media, and cannot be switched off.

Closed Captions – these exist on a separate track to the media being displayed, and therefore can be toggled on or off. This is perhaps the most common type of captions, available on most streaming services.

So, captions and subtitles. We know what they are and have seen them on our screens. Whilst they may be ubiquitous now, this wasn’t always the case.

From the silent era to required by law: A brief history of captions

Emerson Romero, was an early film actor and a Charlie Chaplin impersonator in the 1920s. He was also deaf, and with the rise of the ‘talkies’ found that the deaf community was now largely excluded from watching movies, since there was no longer an onscreen version of the dialogue being spoken. Though he pioneered captioning using some relatively crude technology, it was not widely adopted at first, and didn’t become a legal requirement in the US until 1958.

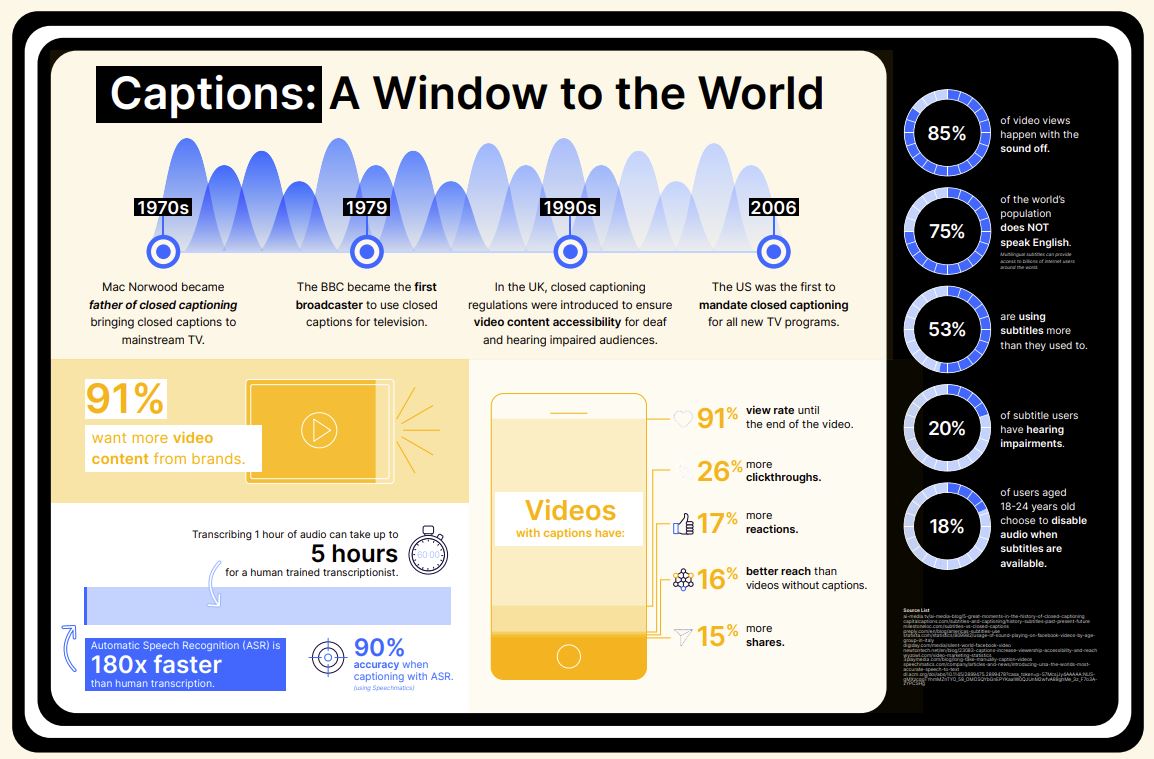

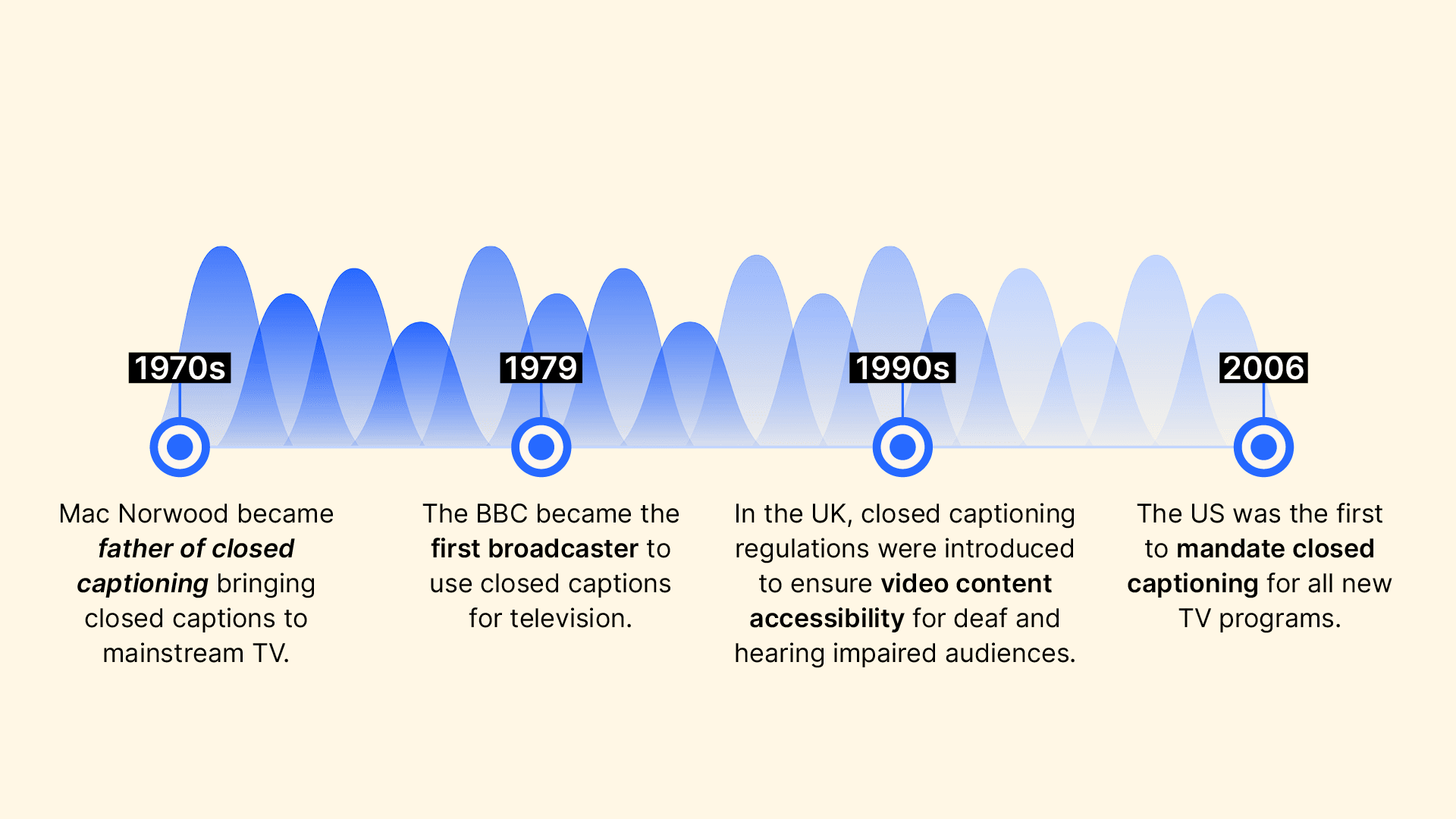

A couple of decades later, Mac Norwood, in his role as US Department of Health, Education and Welfare in the 1970s, brought closed captions to mainstream television. He was then dubbed the father of closed captions. He was a deaf man and understood the importance of reserving the 21st line of television screens for captions. Regular open-captioned broadcasts began on PBS's The French Chef in 1972.

In 1979, the BBC became the first broadcaster to use closed captions for television. Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals could finally watch selected shows with captions from their homes, thanks to the caption ‘decoders.’ These were very clunky boxes that could be attached to televisions and were first sold by Sears in the US in the 1980s.

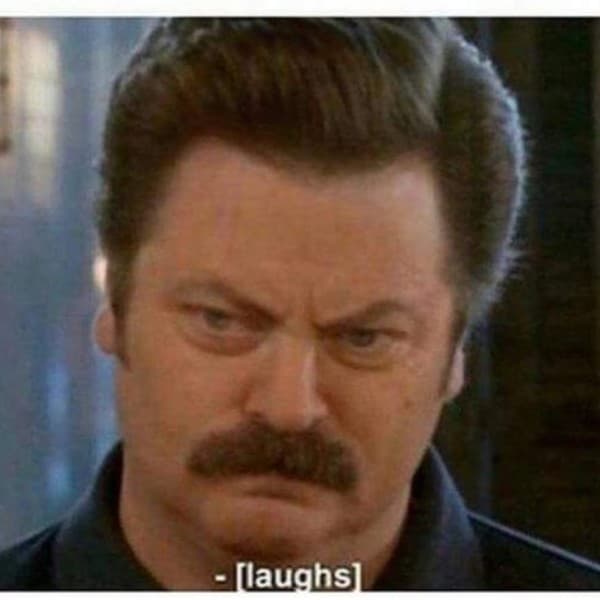

Live captioning came next, with the Academy Awards in 1982 becoming the first live event to have captions to accompany it.

Closed captioning regulations were introduced in the UK during the 1990s to prioritize video content accessibility for audiences who are deaf or hearing impaired. In 2006, the United States became the first country to mandate closed captions for all new TV programs.

The journey to have inclusive and accessible captions on television, film, and media has therefore taken decades, with technological advances enabling them to be more widely available over time. This being said, captions are still not mandated globally with countries like Germany not having regulated captioning standards or requirements that apply to all channels. The availability of captions is increasing over time though, and this global trend shows no sign of abating.

Quite the journey. But do people widely use captions?

Yep. Probably more than you think.

The rise and rise of captions and subtitles

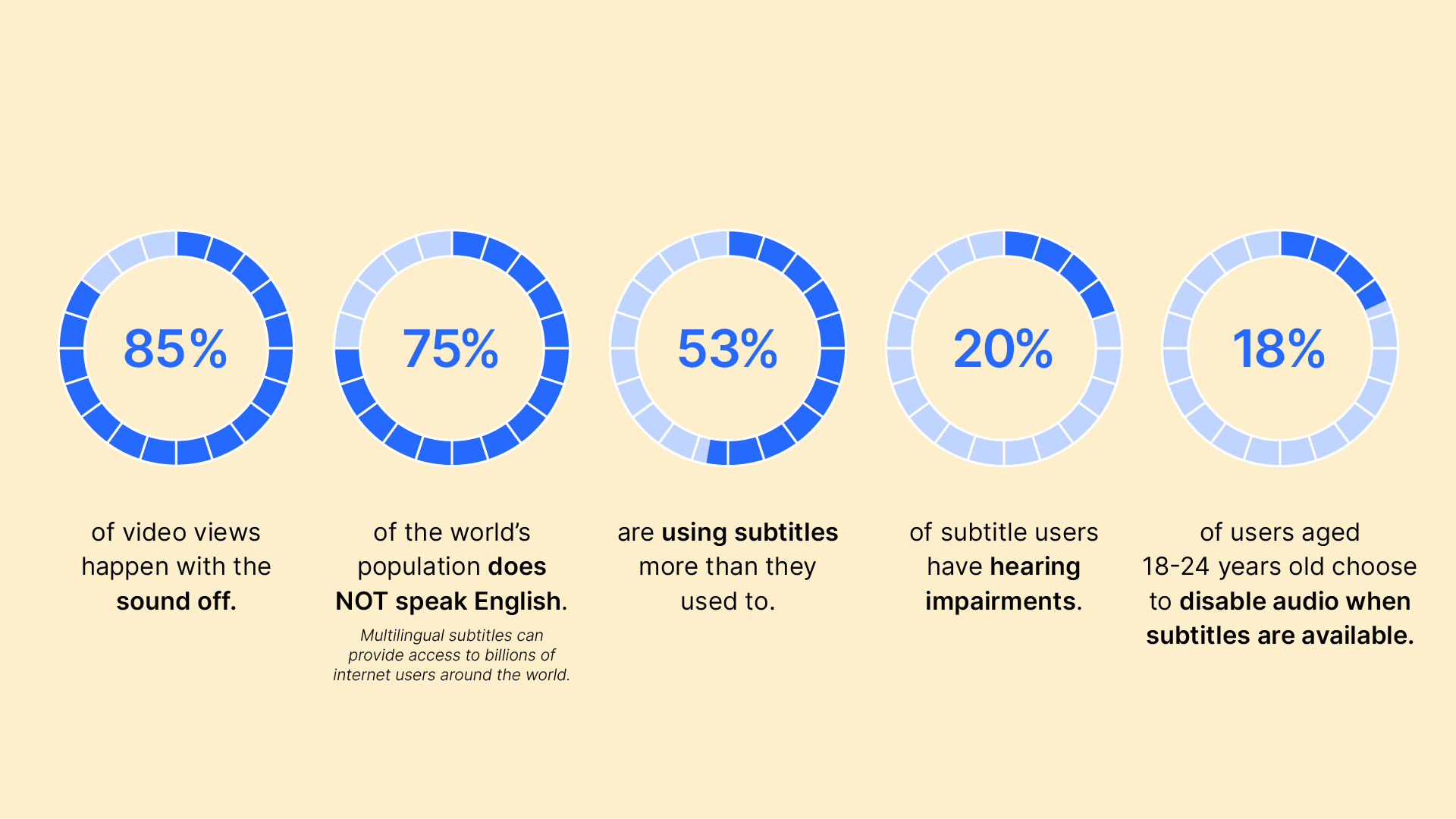

First, a sobering stat for anyone that works in sound editing for video. 85% of all videos on Facebook are watched with the sound off. To understand this ostensibly surprising statistic, you only have to think of where a lot of video watching happens – on a mobile device.

This means that the quiet, noiseless background many are accustomed to at home might not be the case – this could be on public transport, in an office environment, or somewhere where having the sound play loudly from their phone speakers might make them unpopular. This preference is especially strong in the 18 -24 age bracket – 18% of whom will actively choose to disable audio when subtitles or captions are available.

There’s several factors at play here, including:

Popularity of non-English content

Did you watch Squid Game? So did a lot of other people. 65 billion hours of Squid Game were viewed in the first 28 days of its release, making it the biggest hit ever for Netflix. Money Heist, All of Us Are Dead, Parasite, and other smash hits also were not in English; their popularity probably contributing to the familiarity of having subtitles or captions on the screen.

Second screening

Why consume one piece of media, when you can double up? So-called second screening – where you do something on a mobile device at the same time as watching something on a larger screen in front of you also means that you have to pick one audio – people might be able to switch attention from one to the other, but nobody can listen to two things completing for your ears. Second screening increases the likelihood that captions will be necessary on the mobile device.

Mobile viewing (often in public places)

Nothing is more embarrassing than opening up TikTok at work and immediately letting the office know what you’re up to by having the sound blare out. Much video content is consumed in public spaces, and for those not wanting to share what they are watching, whether it's TikTok trends or Instagram reels, captions are a discrete option.

Benefits for children

A more wholesome reason to switch on captions – there are numerous benefits for children – they improve literacy, boost comprehension, help focus, AND provide more inclusivity for children who might not be able to hear the dialogue.

Working content harder

Producing content isn’t easy, or cheap. For every piece of content created, creators want the broadest possible audience. A broad audience means more views, more engagement, wider reach, and given that 5.5 billion people do not speak English (and that’s just English) – providing captions and subtitles in additional languages can ensure that your content is consumable by a much wider audience.

There’s additional commercial value that can be improved with captions too:

So, there's plenty of pragmatic reasons to provide captions for media too.

Captions and subtitles provide enormous value, both to the viewer and to the company that owns the media. They are great for engagement, but also for accessibility.

Sounds like a win, win.

More demand, but how can you provide great captions?

Providing captions and subtitles can be a very resource intensive endeavor. The BBC in the UK for example employs over 200 English-speaking subtitlers, who between them produce over 200 million words of subtitles every year.

You can see more on how they do this here:

Fascinating though this is, many organizations are not in a position where they can employ large teams of transcribers for all of their media. Given the sheer quantity of media created (even outside the media space), this is an overwhelming burden on resources.

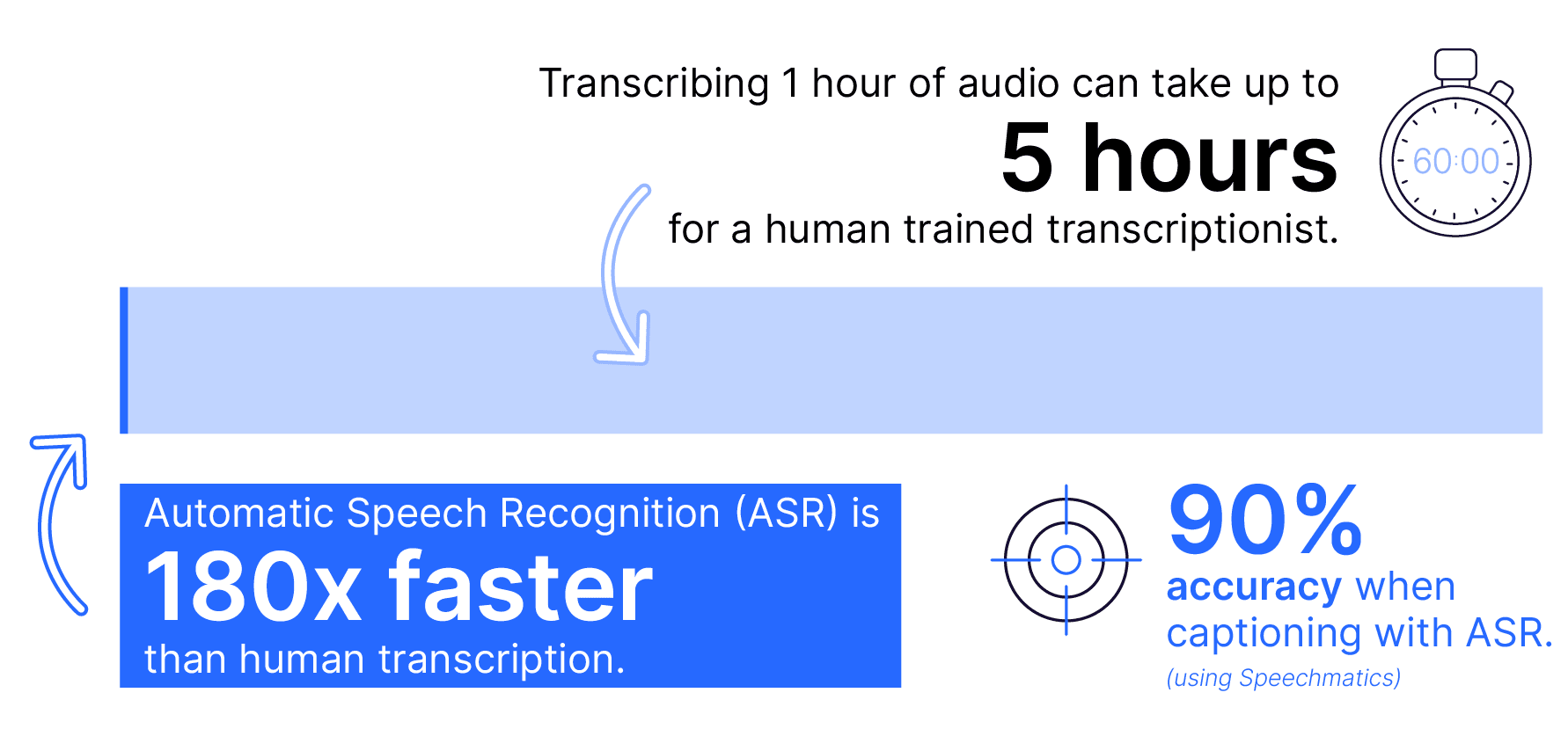

For many organizations, the solution lies in technology, and specifically automatic speech recognition (ASR), otherwise known as speech-to-text.

This approach does not rely on human transcribers but instead uses machine learning to recognize human speech and transcribe it automatically.

Anyone who tried voice recognition technology in the 1990s and early 2000s will know that this technology has not always been easy to use. Now, however, we are at a stage where speech-to-text technology is accurate enough to surpass human-level accuracy.

This means that vast amounts of media can be transcribed (and therefore captioned) in a fraction of the time it would take for humans to complete the job:

Modern ASR APIs can provide a cost-effective, efficient, and automated way to gain the many benefits highlighted above without compromising on the quality of captions provided to viewers.

Many providers now also offer far more than high-quality transcription, with the ability to transcribe in real-time for when speed is important, power captions in multiple languages, and even translate accurately too.

Sound interesting? Well, your journey may have only just started, but we know a great place you can take the next step.

Related Articles

- Use CasesJul 25, 2023

Caption Chaos | Hilarious Times Captions Got It Wrong

Jacqueline PetitjeanDigital Content ExecutiveMaria AnastasiouEvents & Customer Marketing Lead - Use CasesJul 20, 2023

Closed Captioning vs Open Captioning in Media Distribution

Tom YoungDigital Specialist - Use CasesJan 19, 2023

Q&A with Red Bee Media’s Tom Wootton: A First-Hand Account of Speech-to-Text in Media Captioning

Ricardo Herreros-SymonsChief Strategy Officer

Latest Articles

![[alt: Bilingual medical model featuring terms related to various health conditions and medications in Arabic and English. Key terms include "Chronic kidney disease," "Heart attack," "Diabetes," and "Insulin," among others, displayed in an organized layout.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F3I31FQHBheddd0CibURFBv%2F4355036ed3d14b4e1accb3fe39ecd886%2FArabic-English-blog-Jade-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Product

Speechmatics achieves a world first in bilingual Voice AI with new Arabic–English model

Sets a new accuracy bar for real-world code-switching: 35% fewer errors than the closest competitor.

SpeechmaticsEditorial Team

![[alt: Illuminated ancient mud-brick structures stand against a dusk sky, showcasing architectural details and textures. Palm trees are in the foreground, adding to the setting's ambiance. Visually captures a historic site in twilight.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F2qdoWdIOsIygVY0cwl8UD4%2Fe7725d963a96f84c87d614ccc6cce3c6%2FAdobeStock_669627191-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Product

Your voice agent speaks perfect Arabic. That's the problem.

Most voice AI models are trained on formal Arabic, but real conversations across the Middle East mix dialects and English in ways those systems aren’t built to handle.

Yahia AbazaSenior Product Manger

Technical

How Nvidia Dominates the HuggingFace Leaderboards in This Key Metric

A technical deep-dive into Token Duration Transducers (TDT) — the frame-skipping architecture behind Nvidia's Parakeet models. Covers inference mechanics, training with forward-backward algorithm, and how TDT achieves up to 2.82x faster decoding than standard RNN-T.

Oliver Parish Machine Learning Engineer

![[alt: Healthcare professionals in scrubs and lab coats walk briskly down a hospital corridor. A nurse uses a tablet while others carry patient charts and attend to a gurney. The setting conveys a busy, clinical environment focused on patient care.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F3TUGqo1FcOmT91WhT3fgbo%2F9a07c229c11f8cbe62e6e40a1f8682c7%2FImage_fx__8__1-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Use Cases

Why AI-native EHR platforms will treat speech as core infrastructure in 2026

As clinical workflows become automated and AI-driven, real-time speech is shifting from a transcription feature to the foundational intelligence layer inside modern EHR systems.

Vamsi EdaraFounder and CEO, Edvak EHR

![[alt: Logos of Speechmatics and Edvak are displayed side by side, interconnected by a stylized x symbol. The background features soft, wavy lines in light blue, creating a modern and tech-focused aesthetic.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F7LI5VH9yspI5pKWFeiZBXC%2F92f6a47a06ab6a97fb7f5a953b998737%2FCyan-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Company

One word changes everything: Speechmatics and Edvak EHR partner to make voice AI safe for clinical automation at scale

Turning real-time clinical speech into trusted, EHR-native automation.

SpeechmaticsEditorial Team

![[alt: Concentric circles radiate outward from a central orange icon with a white Speechmatics logo. The background is dark blue, enhancing the orange glow. A thin green line runs horizontally across the lower part of the image.]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fimages.ctfassets.net%2Fyze1aysi0225%2F4jGjYveRLo3sKjzBzMIXXa%2F11e90a40df418658e9c15cb1ecff4e4b%2FBlog_image-wide-carousel.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Technical

Speed you can trust: The STT metrics that matter for voice agents

What “fast” actually means for voice agents — and why Pipecat’s TTFS + semantic accuracy is the clearest benchmark we’ve seen.

Archie McMullanSpeechmatics Graduate